I haven’t written a blog for a while because, ironically, I have been busy writing.

Almost five years ago, living in Houston, Texas, I was trying to find courses to improve my art writing. I had written some articles for Arts & Culture Texas and really enjoyed it – after all what is more exciting than being invited to a press preview and being led around by Mona Hatoum (see my review of the 2017 exhibition Terra Infirma at the Menil Collection here).

Mona Hatoum, Homebound, 2000 installation at the Menil, Houston, 2017

Some purists argue that art critics should evaluate artworks without giving thought to the intentions of the artist. Shouldn’t the artwork be able to speak for itself? I am not in that camp. I believe the artist’s thoughts are invaluable: artworks offer a unique chance to get a peak into someone’s mind. What struck me most when listening to Mona Hatoum was how she was led by the specific time and place in which she made her artworks: a residency in rural France peaked her interest in making domestic objects on an industrial scale, a stay in Japan in led to her meditative, contemplative sand drawing sculptures. People, Places and Things are important.

As for the art writing courses – I didn’t find any. What I did find was a course called ‘Memoir - First Page.’ At that point ‘memoir writing’ was a new concept for me; something that only elegant French women did. I have meanwhile learnt that ‘memoir’ is the biggest growing category in book publishing, that almost all literary magazines have a non-fiction category, and that it is also called ‘Life Writing’, ‘Creative Non-Fiction’, “Narrative Non-Fiction’ and ‘Personal Essay’. Where an autobiography is someone’s life told chronologically, a memoir shines a light on a specific period or theme in someone’s life. It is often more complex in terms of craft: using flashbacks, interweaving interviews or research, using imagination and fragments and other literary tropes (my favourite book on narrative structures is Jane Alison’s “Meander, Spiral, Explode’).

Berhe Morisot. Woman and Child on the Balcony, 1872, Oil on canvas, 61.0 × 50.0cm, Artizon Museum, Ishibashi Foundation,Tokyo

My first page for the Houston memoir course consisted of two parts. The first part was an account of an accident I’d had on the morning of my eighth birthday party, when, so excited for my guests to arrive, I’d run straight through our floor-to-ceiling patio doors, the thick, sharp glass slicing my femoral artery. The only reason I am here today is that my parents were both doctors, my father a practising surgeon. Without time to call an ambulance, my mother drove our new blue Hondah through all the red lights, with me stretched out on my father’s lap in the backseat like a modern day Piéta. Except my father wasn’t mourning my death but trying to keep me alive, pressing his thumb on my thigh with force.

The second part was about my admission to a very different sort of hospital shortly after my fortieth birthday: The Priory North London. I described how I was disoriented and confused. How, without a visible injury, I felt guilty: that I had abandoned my two young children, that I had done this to myself. The nursing staff watching me 24/7 didn’t make things better. They wrote notes in their books and made jokes to colleagues in the corridor outside my room. The way in which they treated me showed to me that they doubted my illness too. What is a young woman with a handsome husband and two beautiful children, an apartment in Hampstead and several degrees, doing on the psych ward?

My first page was well received. After I’d read it out aloud, my tutor asked me a question.

“I’m wondering what it was that got you in the hospital, what kind of trauma?”

I hadn’t answered him, just looked at him, perplexed. “There was no trauma”, I replied. “That’s the point of the piece.”

A sensation of anger welled up inside of me. This was the typical reply of people who hadn’t experienced mental illness: cause and effect; trigger and release. And yet for me, depression had engulfed me for the first time when I was twenty, and come back in waves during my late thirties. But then, on my way back from the course, I started wondering if maybe the tutor had a point. What if there was something that had caused my depression? Wouldn’t that be liberating? After all, it would mean that I could take control of my life.

“Life is made of stories,” Joan Dideon wrote in her famous essay On Keeping a Notebook from her 1968 collection ‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem’ “the stories we tell others and the stories we tell ourselves.” And so I started writing, taking online courses during lockdown, working with great mentors (thank you Lilly Dancyger and Peter Mountford and Jonathan Callard).

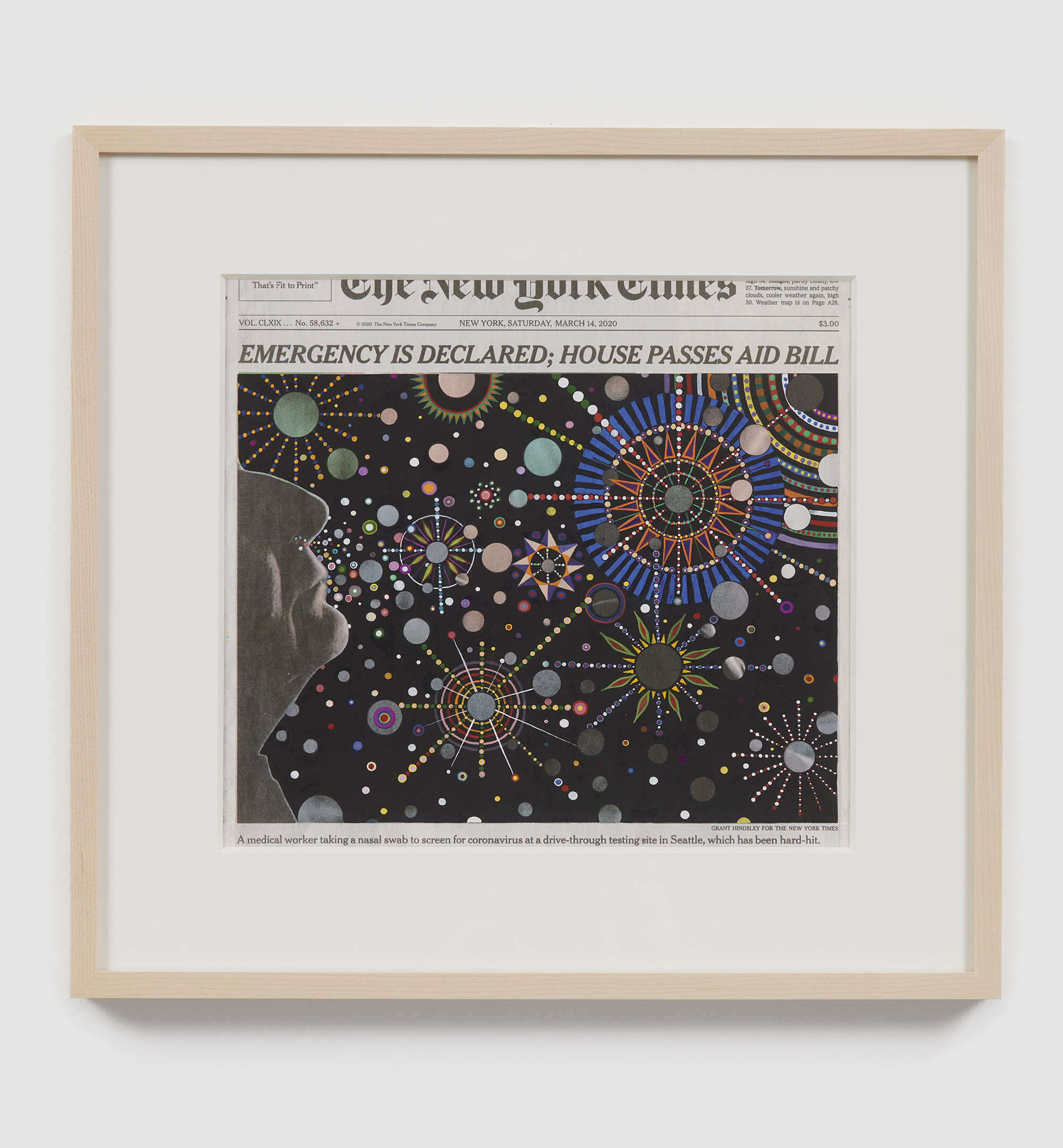

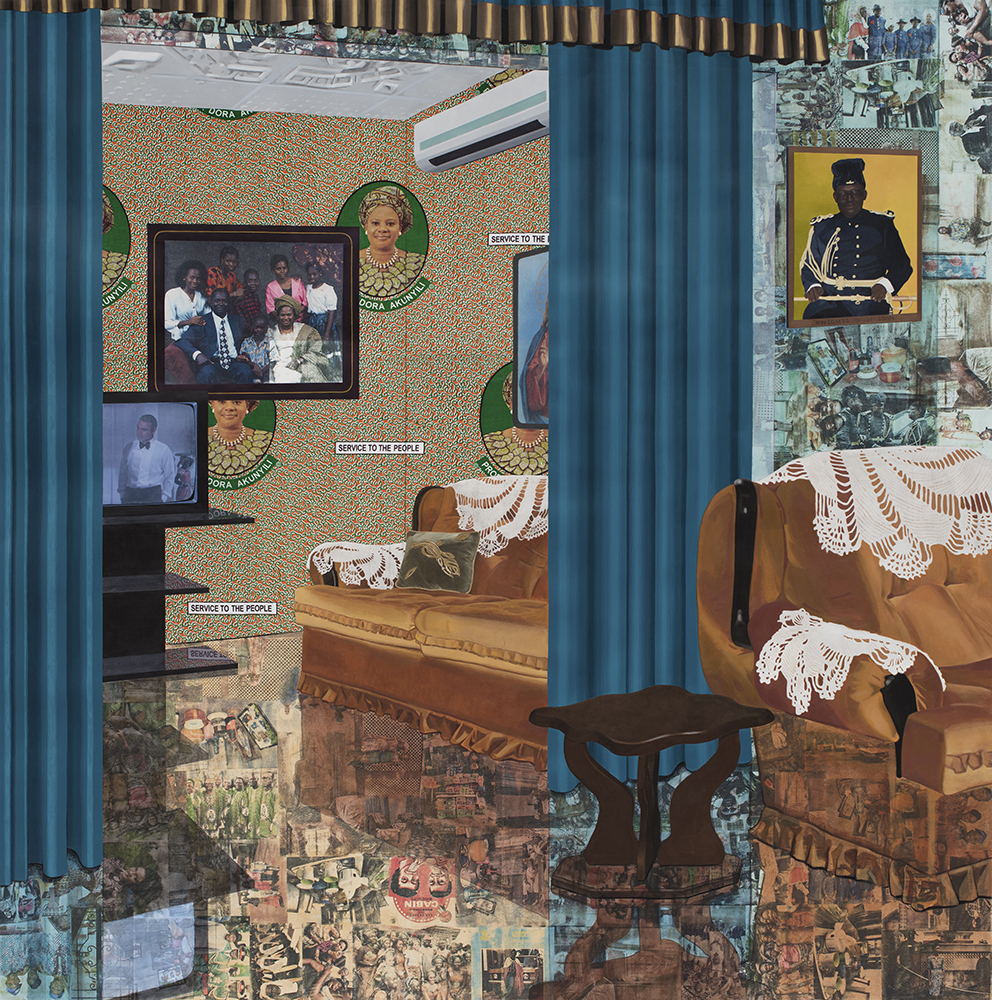

Last year came my first success: a third place in the Fish Memoir Prize for my short memoir ‘Escape Van’ about my depression and camping in Yellowstone and visiting the Plains Indians museum in Cody. A week after I returned from reading that story and celebrating with the other writers at the West Cork Literary Festival, I heard that I was a finalist in US magazine `Fourth Genre’s essay contest, too. My essay ‘Behind the Fence’ about Berthe Morisot and the relationship between my mother and me, and the ways in which women can be held back in their lives was published last month (please see below how to access both pieces).

A year or so after my stay in The Priory, when I finally started to emerge from my depression through a combination of medication, therapy, mindfulness and doing what felt good instead of what I thought others wanted, I read the fictionalised memoir of a Dutch writer: PAAZ by Myrthe van der Meer. She was admitted for five months in the psychiatric ward of a well-known, state-funded hospital in Amsterdam. I remember feeling a pang of jealousy turning the pages, at the easy jokes between the Dutch staff and the patients, the direct way they communicated with each other.

My memoir will be about that. About the pathologising of mental illness at the expense of finding deeper, lasting solutions. About the preference in Western psychiatry for the biological approach at the expense of what psychiatrist Karl Jaspers called ‘the biographical method’, in a 1910 paper in which he described several cases of paranoia in unusual details, paying attention to his patients’ accounts of their lives before they entered hospital and to their subjective experience of their symptoms. Or, as Dr Eleanor Longden, who suffered from hearing voices and spent years on psychiatric wards before becoming a psychiatrist, says in her amazing 2013 Ted Talk ‘The Voices in my Head’: Instead of asking my patients ‘What’s wrong with you?, I ask them ‘What happened?’

My book will also be about art. Ultimately it was my engagement with art that brought me back from my depression: wildly beating on an African drum in The Priory’s music sessions; listening to the songs chosen by other patients. And about stories: hearing other people’s troubles by the lights of the plastic Christmas tree, seated around the coffee table with the puzzle that somehow never got made, like a sad metaphor for our minds. I strongly believe that art has that power to heal, to take us outside ourselves, to teach us something in our lives. Thank you for continuing to follow me on this journey.

For a FREE COPY of the 2023 Fish Anthology containing the 10 winning entries in flash fiction, memoir and poetry, email me the addresses of two people who you think may be interested in my newsletter! sabine@sabinecasparie.com

The 2023 Fish Anthology is avalaible to order on Amazon for £9,-

My story ‘Behind the Fence’ in Fourth Genre’s 2024 Spring Issue can is available on ProjectMUSE for $5,-, or you can subscribe to this great magazine here.

West Cork Literary Festival, 2023