Whilst Frieze dominates the London art world this week, it is important not to forget the art that is happening in London’s smaller galleries. Two interesting shows, one in London and one in Houston, deal with the questions we face in a digital age. In a time where people spend up to 10 hours per day looking at screens, it is not surprising that the screen is becoming a focus for artists’ formal and conceptual exploration.

London’s The Ryder, the exciting art project space run by Pati Lara, is showing two young artists, Thomas van Linge and Vivien Zhang, in a show called Digital Natives. Whereas the work by Van Linge is sleek, uplifting and playful, Zhang is the artist who really delves into the digital. Zhang has only just graduated from London’s Royal College of Art, but already her paintings are showing great depth and intelligence.

As a starting point for her paintings in oil and spray paint, Zhang uses a single motif that she repeats. She has a special affinity for the mathematical shape gömböc, African furniture from her childhood and crumpled aluminum. But interestingly, she does not use these symbols to convey meaning; she uses them instead as contemporary characters, alive in a digital fairytaleworld.

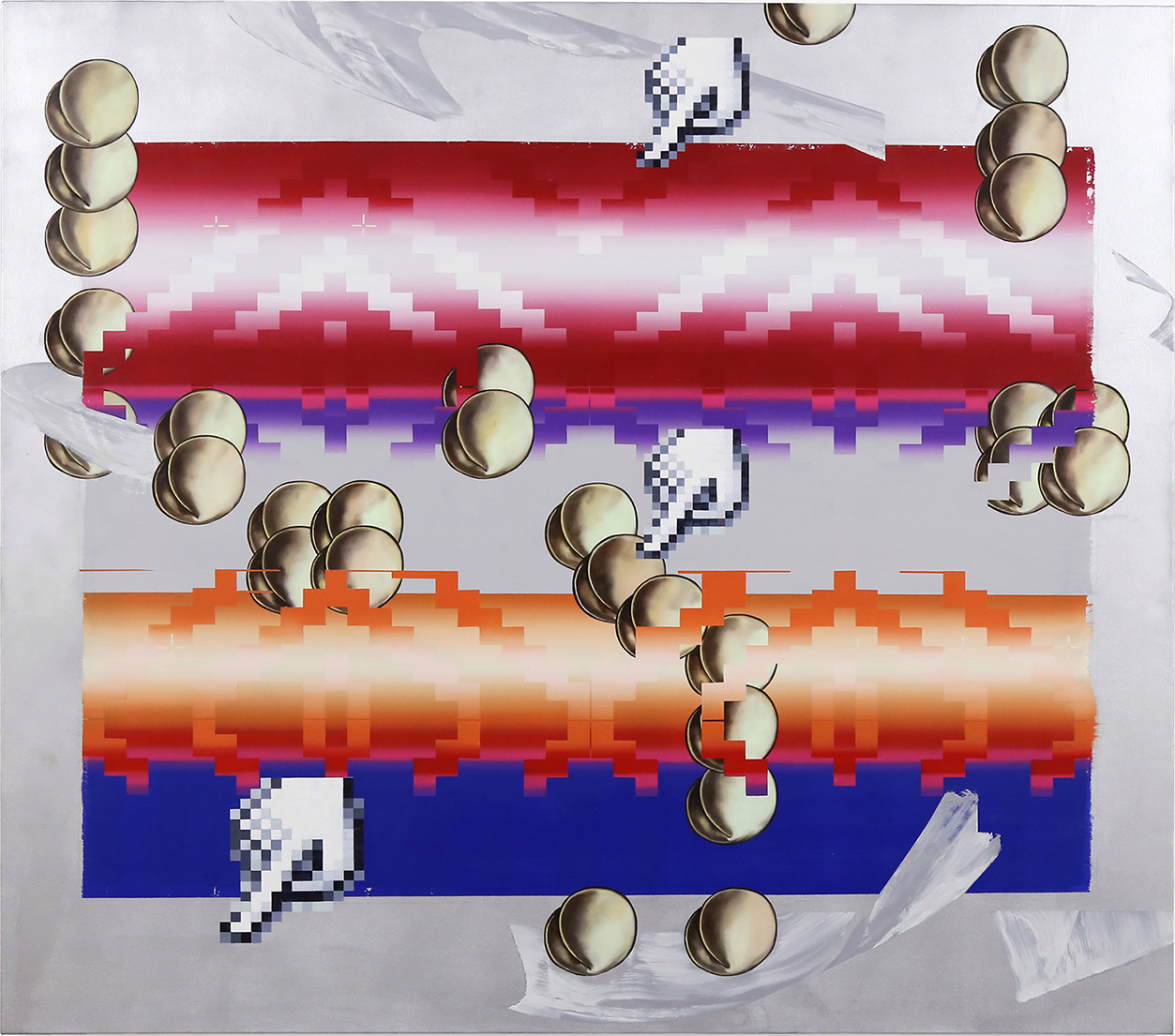

Vivien Zhang, Contra Prunus, 2017. Oil and spray paint on canvas, 140 x 160 cm. Courtesy The Ryder

In Contra Prunus the symbol is the prune, inspired by the paintings of Italian artist Carlo Crivelli (Zhang just finished a residency at the British School in Rome). Various golden prunes are dispersed over a coloured, geometric background that resembles Persian carpets (Zhang's gömböc symbols). The image defies all painterly logic. There is no foreground or background, no perspective and a myriad of painting styles. The prunes are perfectly formed as if taken from a 17th century still life bowl. They float over, behind and inside the pattern, which itself seems superimposed on another background, light-grey with swirls of paint floating on it. And to add further confusion to our perceptive sense, there are three hand symbols, taken from the Photoshop program.

This really should not work. But the strength of Zhang is that her paintings are strangely compelling. You feel drawn into her world, as if you are sucked into a computer and allowed to take a fantasy ride through its algorithms and digi-bytes. Zhang’s world is refreshingly free of ambiguity; narration and representation make way for a new language. In her own words: “(t)he juxtaposition and layering of motifs in my work often follow algorithms found in digital imaging tools – a process by-product of our ways of reading and engagement with visual material today”.

Importantly for Zhang, her painting language corresponds to new hierarchies and relationships that exist in our trans-border society. Having grown up in China, Kenya and Thailand, Zhang can see beyond our current polarities and fixations on borders. She finds the equivalent to a better society in the realms of the digital.

In Houston, another ‘digital native’ caught my attention. Guerrero Projects – a brand new Houston art space opened in 2016 and showing mainly Latin American artists – is showing work by Columbian artist Santiago Pyniol in a show titled Screaming at the Screen. Pinyol’s works are all literally screens: instead of a canvas Pinyol uses shop-bought A4 sized frames, which he installs in grid-like formations. The transparent backgrounds are marked with clear geometric shapes executed in black and white, or in bright-coloured enamel.

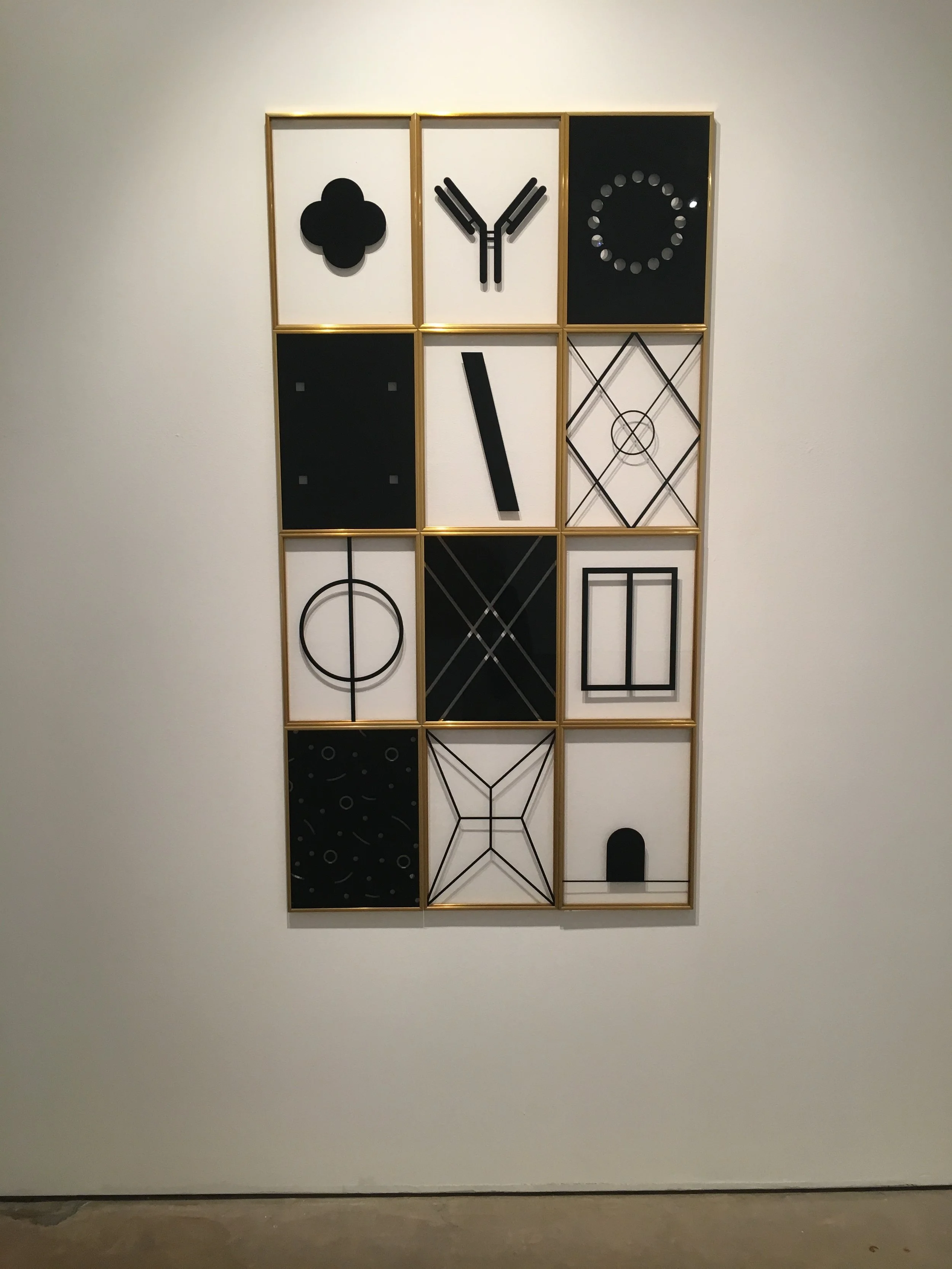

Santiago Pinyol, Mood Board

Mood board is a three-by-three panel grid of plexiglass screens; each screen displays a symbol derived from computer programs such as InDesign. There is the loading icon, the symbol for a virus, a backslash, and, in a playful touch, the mouse is represented as a mouse hole. In themselves, these symbols are simple, plain even. But put together and delineated by the panels’ gold frames, the work takes on a more monumental quality. There is a reference to stained glass, with the total arrangement of panels in Mood Board roughly equivalent to the size of a church window.

Santiago Pinyol. History of the Screen 1 and 2

But the iconography of Mood Board is all but traditional: it is the religion of our computers. To see something that is usually glanced over quickly on a screen hung in this way on a gallery wall really plays with our preconceived ideas about the distinction that exists between ‘computer symbols’ and ‘art’. It is almost difficult to look slowly at this work, to leave the associations we have with these symbols and consider them in a new light, as artistic shapes in a larger composition.

The connection between screens and windows is even stronger in History of the Screen 1 and 2, where two panels are displayed in a corner composition. Pinyol deliberately plays around with his screen compositions, to emphasize their interchangeability and allow the viewer of the work the same freedom that exists when maneuvering a computer screen. Pinyol does make a distinction between ‘art’ and ‘design’ – to him they are both valid as art forms.

Like Zhang, Pyniol is an artist who makes imaginative use of our contemporary digital language as a material for art and as a means to explore our world. But where Zhang’s works are two-dimensional, Pinyol treats his frames as objects, thus forming a type of semi-sculptures out of the flatness of the screen. In History of the Screen 1 and 2, light is beautifully reflected giving the work a serene feel. These screens are, like digital screens, a window to an infinite world of information, connectivity and knowledge.

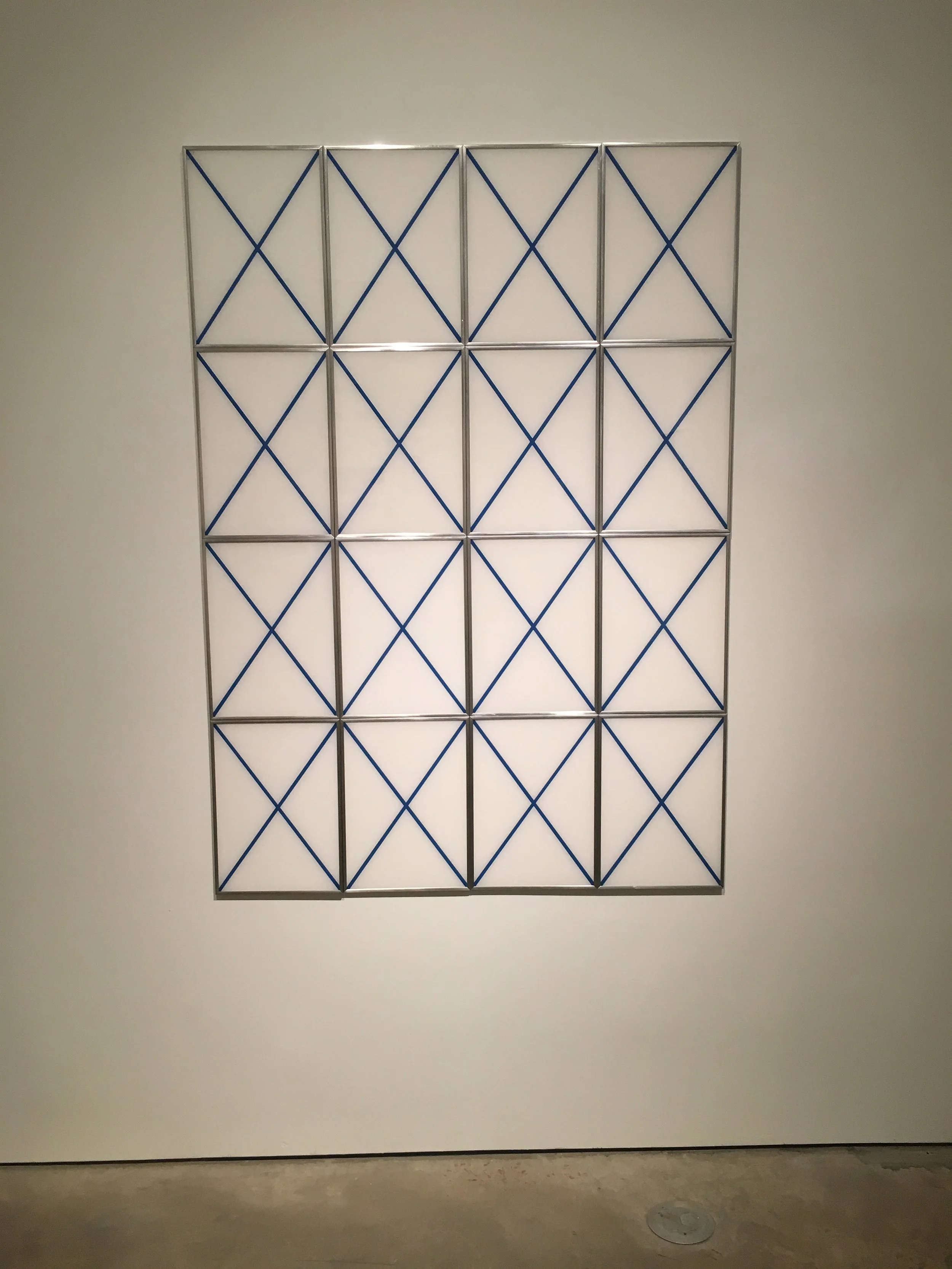

Santiago Pinyol’s large, window-sized work in the back room of the gallery consists of twelve transparent panels, each consisting of a blue cross. It is called F.O.M.O.: fear of missing out. This may well be the malaise of our times, where everyone else’s life appears like a shiny compilation of beautiful beaches, crazy parties, high-flying careers and photogenic children. But it also captures our digital world, where to be connected, is to be alive. We need to look to young artists, our ‘digital natives’, to rejuvenate the language of art, and at the same time offer a meta-commentary on our existence in the digital age

Santiago Pinyol, F.O.M.O.